We've all heard of an apple core. It's the part of the apple most people throw away. Today, we hear about a different kind of core - a core sample of the Earth. The University of Kansas recently dedicated more space to store and display these rock core samples. Commentator Rex Buchanan tells us why.

(Transcript)

Getting to the Core of Kansas Geology

By Rex Buchanan

A friend of mine once said that there’s more history in a square yard of Kansas soil than in all the history books in all the world’s libraries.

That might have been a bit of hyperbole, but he had a point. No matter where you stand in this state, there’s hundreds of millions of years of geologic history beneath your feet.

And what’s down there matters. The subsurface is not just a record of the geologic past, of the oceans and glaciers and erosion that shaped this place. It also holds geologic resources, like groundwater, oil and gas, and minerals, that we all depend on.

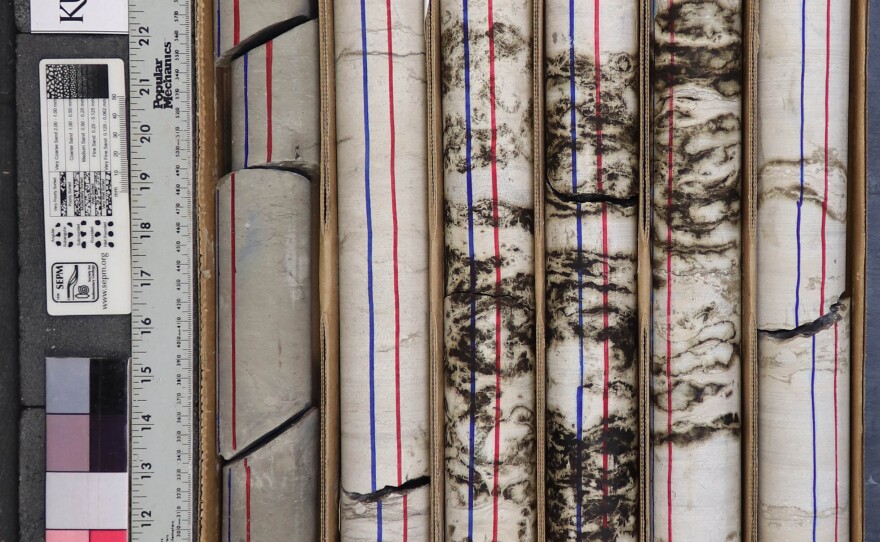

A few weeks ago the Kansas Geological Survey here at KU, where I still work part-time, dedicated a new building addition that provides more space for core samples. Cores are cylindrical-shaped rock samples, a little bigger around than, say, the handle of a baseball bat, pulled up to the surface by a drilling rig.

Because coring is expensive, drillers generally don’t recover cores from wells. So when they do, those samples are exceptionally valuable. That’s because a core is a complete, intact record of what the drill bit encountered in the deep subsurface where none of us can ever go or see firsthand.

Those cores, and the fossils they contain, tell us much about the environment when the sediments, which became rocks, were laid down. And cores are especially valuable in mineral and energy exploration, telling geologists and engineers what kind of minerals, fluids, and gasses they can expect to encounter in a given area.

They can even save lives. In 2001, natural gas escaped from a storage facility near Hutchinson, moved underground, then exploded back up to the surface, killing two people and damaging buildings. Core from that area was key to understanding how the gas had moved. Overnight, samples in the Survey’s core collection became just about the most valuable rock anywhere in the state.

You never know how cores will be used, what they’ll reveal about the subsurface, what resources they’ll help unlock. So keeping them is critical. Each is one of a kind. Unlike a regular library, which generally houses books that are duplicated in other libraries, each sample in a core library is unique and thus irreplaceable.

And they’re cool to look at, displaying small fossils and layers of sparkling minerals such as calcite. Each core is a glimpse of rock that hasn’t seen the light of day for millions, sometimes hundreds of millions, of years. The first person to look at that core is the first person to ever see those rocks.

I’m not sure that most people, including geologists, really comprehend the concept of deep time, of millions and millions of years, and the duration of events in the geologic past. But one place deep time does reveal itself is in these core samples. So maybe my friend was right. Maybe each core does contain a record that far exceeds the history we’re more familiar with. Records of seas and deserts and fantastic plants and animals. Of time beyond imagination. ###

Commentator Rex Buchanan is a writer, author and core sample enthusiast. He's also director emeritus of the Kansas Geological Survey at the University of Kansas. He lives in Lawrence.