Black and white photos and films from the 1930s show drifts of dirt overwhelming fences, tractors and even farm houses throughout the Great Plains.

Nearly anyone with family who lived through it has heard the stories.

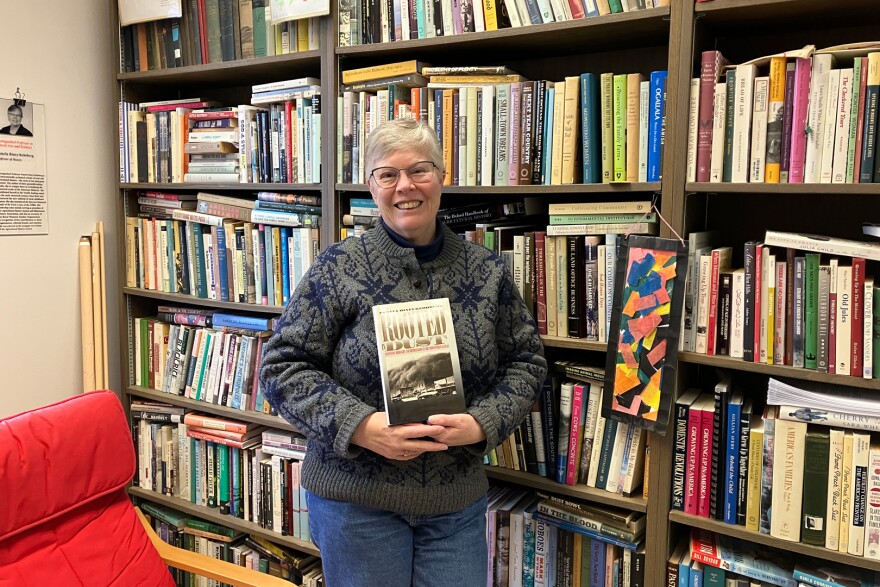

Pamela Riney-Kehrberg’s grandparents lived in southwest Kansas and recalled how nothing escaped the dust.

'“One of the things my grandmother told me was that she would go out and put the clothes on the line every morning before the sun came up so that hopefully, the clothes would have a chance to dry before dawn came and the winds came up and everything — just all her work got destroyed,” Riney-Kehrberg said.

At the height of the fierce dust storms in the mid-1930s, more than 1.2 billion tons of soil blew away.

This spring marks the 90th anniversary of the federal agency that was born out of that ecological disaster, what’s now known as the Natural Resources Conservation Service. Yet after nine decades, the NRCS is facing an uncertain future.

The agency has lost as much as 20% of its workforce, with estimated job losses reportedly surpassing 2,400 employees, since President Trump took office. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, which oversees NRCS, is also considering plans to consolidate NRCS county offices and its programs with other agencies.

Meanwhile, Trump’s budget recommendations for the next fiscal year include trimming $754 million from NRCS private lands conservation operations and another $16 million from watershed operations.

Soil conservation’s roots

On April 14, 1935, one of the worst storms of the Dust Bowl rolled over the landscape. Black Sunday covered an area about 800 miles long and about 300-500 miles wide, stretching from central Nebraska down to Texas, and hitting the Oklahoma and Texas panhandles hardest.

Although it started as a calm Sunday morning, a cold front picked up wind speeds and dropped the temperature later in the day. A 500-600 foot wall of dust and sand came from the north moving at speeds of more than 50 miles per hour.

Hundreds of birds flew ahead of the rolling dark dirt and a number were found dead after the storm. In Kansas, 17 deaths were reported from dust pneumonia and three died from dust suffocation, according to the National Weather Service. The storm caused widespread damage and when it finished, an estimated 300,000 tons of soil had left the Great Plains.

Riney-Kehrberg, who teaches history at Iowa State University, said lawmakers could no longer ignore what was happening in the central U.S. Dust from the storms was at times darkening skies over East Coast cities, including Washington, D.C.

“It took a little while for the people in Washington to get really concerned,” Riney-Kehrberg said. “And yes, that dust storm that arrived in Washington, D.C. really upset people, because here was evidence that something had to be done.”

That same month, lawmakers passed a bill creating the Soil Conservation Service, the precursor of the NRCS.

The government was now able to pay farmers to leave some of their fields fallow and to put new soil practices in place, such as crop rotation, contour plowing and terracing hillsides.

“It was not hard to get people on board with these conservation practices because they were desperate,” Riney-Kehrberg said. “They were going to lose their farms if they didn't find an alternate form of income, and if you are desperate not to lose your farm, you were going to cooperate.”

In the agency’s beginning, Kevin Norton said a huge amount of work went into transitioning marginal lands back to grass, as well as helping change the mindset of farmers to think more about conservation.

Norton, who retired in 2021 as the associate chief of NRCS, said the agency adapted over the decades to keep up with the times, the technology and farmers’ needs.

“And it's worked. I mean, we have a lot cleaner air. We have less dust in the air. We have an abundant food supply and less erosion,” Norton said. “So, I think we've got a wonderful system. It's been successful.”

Over his nearly 40-year career with NRCS, he said the demand for its services remained strong among farmers and ranchers.

“I suspect if Congress would fund the programs at twice the level, we would see all of that money put to use on agriculture operations across the country,” Norton said.

Cuts come to the agency

For Carrie Chlebanowski, a former NRCS public affairs specialist in Oklahoma, 2025 has been a tumultuous year.

Despite being promoted in January, she was one of thousands of federal probationary employees who received a termination letter in February citing performance. A few weeks later, a federal ruling reinstated Chlebanowski and other probationary workers, who were instead put on administrative leave.

Chlebanowski said she loved her job communicating about NRCS’ work, but when the second deferred resignation package opened, she took it.

“I’m relieved that I’m done and I’m no longer subject to the chaos,” she said. “But I'm sad and I'm worried for what the future holds for the people that I worked with that I know care so much about the farmers and our soils and the conservation work that they're doing, and just not knowing what that's going to look like.”

According to the most recent data from the U.S. Office of Personnel Management, there were 11,623 employees at NRCS in September of last year. Following this year’s layoffs, deferred buyouts and retirements, that number now hovers closer to 9,200, according to several media reports. A USDA spokesperson would not confirm the exact employee losses, saying the deferred resignation program was recently closed and officials are finalizing numbers.

“We have a solemn responsibility to be good stewards of Americans’ hard-earned taxpayer dollars and to ensure that every dollar is being spent as effectively as possible to serve the people,” the spokesperson said in a statement.

Yet Jamey Wood — who spent much of his career at NRCS — worries not much will be gained by cutting employees.

“They may become more efficient in some little pockets, because they're going to have to focus on the most critical things and get some critical things done,” he said. “But the morale is just in the dumps, you know, from the uncertainty.”

A long-time NRCS district conservationist in Oklahoma, then the state’s acting conservationist, Wood even worked for the agency on a contract basis after his retirement. That ended earlier this year when he was laid off. Wood knows there were already waiting lists at many NRCS offices.

“Producers are requesting conservation plans so they can do better conservation work, so they can participate in conservation programs, so they can get financial assistance to help them do conservation,” he said. “And now, and this is my estimate, you're going to lose basically a generation of conservation planners.”

Kalee Olson, policy manager at the Center of Rural Affairs in Lyons, Nebraska, said the strength of NRCS has been its local ties with farmers and ranchers.

With fewer employees and potentially longer wait times, she wonders whether farmers will choose to let some projects go.

“Let's just say we have a producer who's interested in trying cover crops for the first time,” Olson said. “If there's a longer wait list, so to speak, of getting support from NRCS, that producer might just opt to forego cover crops for that given year.”

Olson said NRCS workers are resilient, and she expects they’ll make every effort to help farmers and ranchers.

“I do think NRCS has really proved themselves to be nimble, and they really do work hard for producers across the state,” she said. “So I don't doubt that they're up for the challenge, but there's just only so many things that any of us can achieve in a day.”

This story was produced in partnership with Harvest Public Media, a collaboration of public media newsrooms in the Midwest and Great Plains. It reports on food systems, agriculture and rural issues.