LAWRENCE, Kansas — Every day, Jessica Glendening expects to receive a list of new criminal cases that need public defenders in the Douglas County District Court.

That list includes all of the new criminal cases assigned to the Seventh Judicial District Public Defender's Office based in Lawrence. The office represents defendants in criminal cases who cannot afford to hire their own attorney — a key component to the U.S. justice system that is enshrined by the Sixth Amendment in the Constitution.

Glendening, chief public defender for the office, said they recently reached a full staff of seven attorneys. That has allowed the office to provide legal services to those defendants as soon as they are charged with a crime.

But that may not last for long. Eventually, the caseload may become too large, and the office will need to stop taking on new cases for a while. Glendening said that would happen when her office was not fully staffed last year.

“We've had to close the office several times,” Glendening said, “because the attorneys were at their maximum caseload.”

When that happens, the pile of cases that need public defenders are offered to private attorneys. Someone like Cheryl Stewart, an attorney based in Oakley on the far west side of Kansas.

She will drive for hundreds of miles from her home to courtrooms in places like Elkhart in the southwest and Topeka in the northeast. She said she could spend up to five hours on the road before she steps into a courthouse. She often needs to spend the night in towns all over the state to be ready.

“I drive to a hotel in that town the night before,” Stewart said. “Last year I had over 33 nights in hotels.”

Stewart loves her job and she doesn’t mind traveling for work. But she can only take on so many cases.

The Kansas State Board of Indigents’ Defense Services must provide public attorneys to people who cannot afford one. But the agency often does not have enough staff at its public defender offices across the state to cover all of its cases and hires private attorneys. If the agency fails to find an attorney, a judge could simply dismiss the case, no matter how serious the charges are.

That’s not yet a problem in Kansas, but it could be if state lawmakers don’t provide the necessary funds to hire the needed attorneys.

It’s already happened in Oregon. The Associated Press reported that nearly 300 cases in the Portland area were dismissed in 2022 because of a shortage of public defenders. Mike Schmidt, the top prosecutor there, called the crisis “an urgent threat to public safety.”

Kansas could avoid throwing out criminal cases by prioritizing public defense and incentivizing new private attorneys in rural areas. But that will cost money.

The lack of public defense attorneys also coincides with a shrinking number of attorneys serving the state’s rural areas. That makes it even harder for the state to find private attorneys to help fill the holes.

The Kansas Judicial Center recently studied the issue and has begun ringing warning alarms.

Chief Justice Marla Luckert recently told lawmakers that the lack of attorneys hurts everyday Kansans who must rely on attorneys when they end up in court. She said it will only get worse if the state does not take action.

“If we are to help these people and avoid an all-out crisis, complacency cannot be our approach,” Luckert said. “We must all put on our hero capes and work together to find solutions.”

Public Defense

A 2023 study conducted by the Board of Indigents’ Defense Services showed that the state’s public defenders are overworked and underpaid.

National standards call for an attorney to work about 248 hours on a murder case. As things stand now, Kansas public defenders only have an average of 13 hours to spend on any given case.

Heather Cessna, the executive director for the Board of Indigents' Services, said that is woefully inadequate and raises ethical concerns about the agency’s ability to provide effective legal counsel.

“The bottom line is we either need fewer cases in our system,” Cessna said, “or we need a lot more attorneys to handle those cases.”

Cessna recently told lawmakers she needs to hire 600 attorneys — 400 public defender staff and 200 private attorneys taking on public cases where the state does not have a public defender office — to properly cover the state’s case load.

Meanwhile, it’s also hard to fill those positions because the agency cannot offer competitive pay.

Consider a prosecutor. They are Kansas employees who represent the state and its laws in criminal cases. They are often facing off in court with a public defender, another state employee tasked with providing criminal defendants with their right to legal counsel.

Cessna said prosecutors earn higher pay, up to 30% more. That makes prosecution a much more attractive job than public defense, despite the two attorneys effectively working the same cases from opposite ends.

Cessna has requested lawmakers provide more funding to help retain her current attorneys and attract new ones. Otherwise, public defenders are earning lower pay to provide a vital service in the U.S. justice system.

“Everybody who is doing this work is sacrificing something because they believe in the Constitution,” Cessna said of public defenders. “They believe in our clients' rights to have somebody there to defend their case.”

Rural attorney shortage

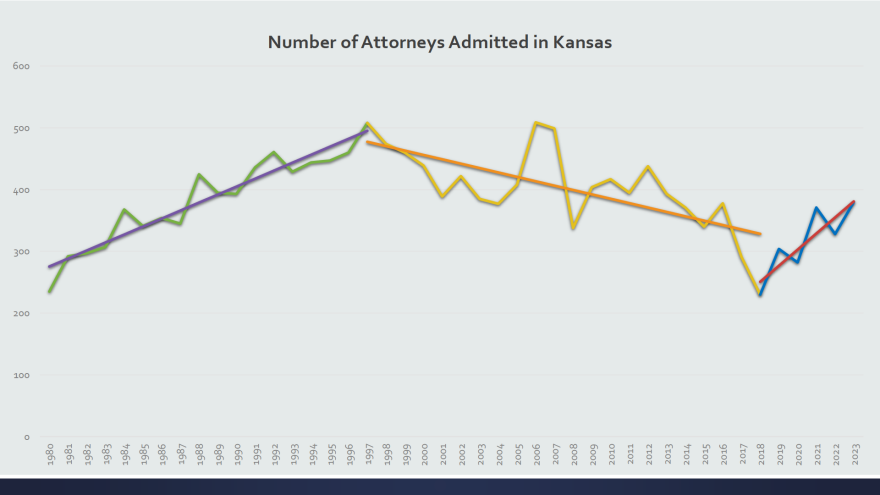

The lack of public defenders is compounded by a shrinking number of rural attorneys.

Private attorneys across the state have long been a release valve for the public defender offices that cannot take on any more cases. That’s very important in rural areas, where there are no dedicated public defender offices.

A Kansas Judicial Branch committee studied why the rural areas are struggling to employ attorneys. They found many young attorneys fear opening their own legal practice in rural parts of the state. That's because of their lack of experience and concerns about making enough money.

In the meantime, the crop of attorneys in the rural areas are aging quickly. The study shows the average age of the rural attorneys in Kansas is 55. That’s nearly 10 years older than the national average of 46.

Kansas Supreme Court Justice KJ Wall, who led the committee, said there are rural attorneys in their 70s who believe they can’t retire because no attorney will come fill the hole they will leave in their communities.

Wall said the problem isn’t just a lack of criminal defense attorneys, but a lack of attorneys serving every aspect of the legal spectrum. That could be family law, estate planning, civil litigation and more.

The Judicial Branch committee has offered solutions, like creating a professional organization to support rural attorneys and working with state universities to attract more students to its law schools.

However, Wall said young attorneys also have crushing student loan debt. He suggested lawmakers provide tuition reimbursements to promote working in rural areas for a certain amount of time.

Kansas already offers student loan reimbursement programs for health professionals who choose to work in areas with health care shortages. The state in 2012 also launched its Rural Opportunity Zones program aimed at attracting residents to move to rural settings.

The state hopes those plans will also help reverse its shrinking rural population. Wall said there’s evidence that a similar program for attorneys can help.

“What we found in other states,” Wall said, “is that those that are participating end up more often than not staying in that same community even after their service commitment ends.”

The rural areas also have an advocate in Stewart. She said she encourages young attorneys to consider working in the rural areas and that she is willing to help them get their footing.

Stewart previously worked in Kansas City, Kansas, but found a much better work experience in western Kansas. That’s partly because the demand for an attorney was much higher.

“My last year of income in Wyandotte County was like $25,000,” Stewart said. “I moved out to Western Kansas and that income doubled in six months.”

Cost of justice

Both Cessna and Wall said that without solutions, the inevitable end result includes courts dismissing criminal cases. That means defendants credibly accused of crimes would not face consequences and victims of crimes may never find justice.

Cessna asked for $4 million to help fill 29 staff positions next year, only a fraction of the many positions her office needs.

So far this year, Kansas lawmakers have not approved funding for a reimbursement program or added money for the state’s public defense agency.

In fact, some Republican lawmakers and Democratic Gov. Laura Kelly are proposing budgets that will not fully cover a nearly $7 million shortfall for the agency this year. The agency will need to offset that loss with funds it saved for positions it wants to fill.

Lawmakers are also proposing no new funding next year. While Kelly offered a meager $1.7 million increase.

That puts the public defender agency in a tough position next year. Cessna said the state already expects her office to see increased expenditures because of the number of cases are expected to be resolved next year to the tune of nearly $5 million.

But Republican Rep. William Sutton of Gardner said lawmakers have to do something. The U.S. Constitution requiring public defense means the state’s hands are tied.

“They either need to have attorneys on staff,” Sutton said, “or they need to be able to contract for them if they're not on staff. Either way that's an outlay of money.”

Lawmakers are still discussing the budget and could make changes before those bills come due.

Dylan Lysen reports on social services and criminal justice for the Kansas News Service. You can email him at dlysen (at) kcur (dot) org.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.