WALLACE COUNTY, Kansas — The Ogallala Aquifer has a visibility problem.

It’s easy to see when drought, farm irrigation and city taps drain the great reservoirs of the Southwest. Bathtub rings paint the red rock walls surrounding Lake Powell as it shrinks, sounding alarm bells loud and clear.

What about a body of water that’s locked away in a subterranean labyrinth of gravel and rock reaching more than 300 feet underground?

The Ogallala may hold as much water as Lake Huron, but we can’t see it. And, problematically, that means we can’t see it disappear.

That hasn’t stopped people like Brownie Wilson from trying to bring the aquifer’s decline into focus. He’s one of the Kansas Geological Survey crew members who fan out across western and central Kansas every year to check hundreds of water wells that tap into the Ogallala.

In Wallace County along the Colorado border, Wilson hikes into a crop field toting a giant spool of measuring tape like it’s a piece of carry-on luggage. He feeds the steel tape down a pipe where it snakes hundreds of feet until it strikes water.

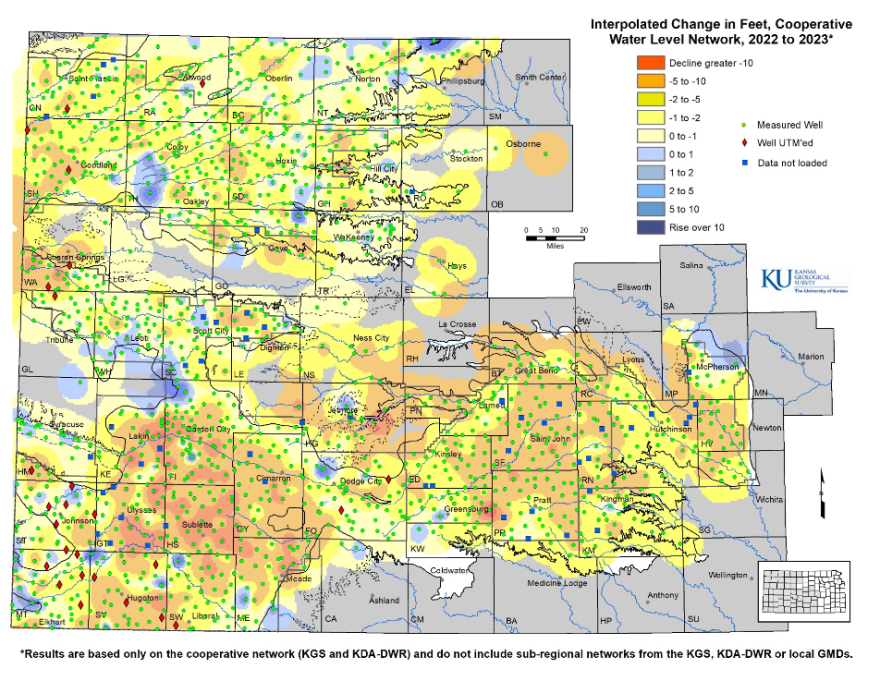

This county has already lost more than 80% of the water in its corner of the aquifer — the highest percentage loss in the state. In some parts of Wallace County, aquifer levels fell seven feet in just the past year. That’s seven feet closer to running dry.

Statewide water levels fell by an average of nearly two feet this year — the third-largest decline since the 1990s — as extreme drought pushed farmers to irrigate crops more than usual.

If the water keeps running out, some of the region’s farms and towns could vanish within a generation or two.

“We’ve still got time in a lot of places,” Wilson said. “In other places, that future is now.”

Many western Kansas farmers have cut back on how much they irrigate their crops — voluntarily. Others have been forced to adapt as their wells run dry. But after decades of mostly inaction from Kansas leaders, a new push to support water conservation at the Statehouse signals that the state may finally be shifting toward a more committed, perhaps even mandatory, approach to saving the Ogallala.

But preserving the aquifer is a tricky balance in these parts. Irrigated farming pays the bills. Rural economies and communities depend on it.

Irrigation also consumes the largest share of the aquifer’s water — by far. Nearly all (94%) of the water used in Wallace County’s regional groundwater management district, GMD 1, goes to irrigate crops. Statewide, the amount of water pumped from underground and sprayed onto crops averages out to more than 2 billion gallons per day.

“When you're talking about groundwater declines, there’s only two ways to fix it,” Wilson said. “You gotta put more water in or you quit taking more out.”

- ‘This is do or die’: Western Kansas farmers push to save the Ogallala Aquifer before it’s too late

- This is the first time the Kansas Water Authority has voted to save what's left of the Ogallala

- Here's how this year's drought has battered the Midwest — and what it might mean for next year

- This city in Kansas really conserves its water, but that still might not be enough to survive

- How Kansas could lose billions in land values as its underground water runs dry

But only a tiny fraction of this region’s meager rainfall ends up refilling the aquifer. In fact, the Kansas Geological Survey estimates that this district’s portion of the aquifer gets used up at nine times the rate that it’s replenished by precipitation.

And the rainfall that does trickle down to the depths can take years to do so because it has to work its way through hundreds of feet of rock. Water that’s finally dripping into the Ogallala’s depths today, for instance, may have fallen as a raindrop a decade ago.

On top of that, several towns near here recently wrapped up their driest year since humans started keeping records. Some areas got only eight or nine inches of water for the whole year. That’s akin to the rain totals you’d see in a desert.

But even though this extraordinarily dry year highlights the aquifer’s dire straits, Wilson said, people who’ve been paying attention to the long saga of depletion in western Kansas won’t be surprised.

“We designed our water policy to make this happen. We permitted all these wells, knowingly,” Wilson said. “That decision was made 40-50 years ago by people who are no longer with us or moved on. But now we’re dealing with those ramifications today.”

Turning the tide

So, how did Kansas end up here?

Decades ago, the state freely handed out water rights. That helped irrigated farming flourish on the semi-arid plains, but has ended up straining the Ogallala more than it can bear. The approach became known as the state’s policy of planned depletion — gradually emptying the aquifer to support farming.

It was good for business. So Kansas leaders have long been wary of limiting irrigation. But recent action shows small steps in a new direction.

The Kansas Water Authority voted for the first time last December that the state should stop draining the aquifer for agriculture. And now Kansas lawmakers have approved a bill that pushes groundwater districts to reduce water use in the areas with the most severe depletion.

The bill would still keep water conservation decisions in the hands of local groundwater districts, which recognize how the aquifer’s depth and capacity — and the potential solutions to preserve it — vary widely from one area to another. But it would force those districts to crack down harder.

The districts would need to identify which parts of their region are in the worst shape — such as spots where the aquifer has fewer than 50 years of usable lifetime remaining — by 2024. Then, the districts would need to submit plans to the state for cutting water use in those areas by 2026. If they don’t do that, the state could step in and decide water conservation plans for them.

Another bill that tried to address some of these same water issues last year died before making it to a full vote. Advocates blamed the agriculture industry for hindering restrictions.

But when this new bill came up for a vote in the House, it passed overwhelmingly — 116 to 6.

It found wide-ranging support among groups that don’t always agree, from the Kansas Farm Bureau and Kansas Livestock Association to the Nature Conservancy.

So what changed? Why did this bill succeed when others have failed? Maybe it’s the ongoing extreme drought. Or the threat of even more state involvement as water becomes increasingly scarce in the future.

Jim Minnix — a Republican from Scott County, right in the middle of Ogallala country, and chair of the House water committee — summed up the urgent situation during one of the bill’s hearings. If Kansas wants to avoid the fate of states farther west, he said, something needs to change.

“We’re here today so that we don’t become what the Colorado River Valley or Central California looks like,” said Minnix, who is also a western Kansas farmer. “We here in Kansas have an opportunity to improve our own future right here. And it starts now.”

To help, the House also passed a second bill that would include millions of dollars for a variety of water-related projects, such as restoring reservoirs and updating small town treatment plants. In the Ogallala region, the bill could fund everything from cost-sharing programs that help landowners install more playa lakes that encourage aquifer recharge to grants that help farmers buy new water-saving technology, including irrigation systems that customize the spray rate based on how much water a certain patch of soil needs.

Just by getting Kansas farmers to universally adopt the current water-saving tools available to them, Minnix estimates the state might be able to reduce its water use by up to 20%. That could mean the aquifer’s around for another 50 or 100 years, he said, depending on how soon more irrigators get on board.

“It’s an issue that I wish we’d started 40 years ago,” Minnix said. “We’d be in a far better situation today.”

But when farming is already a risky, expensive operation, many farmers are hesitant to try something new.

Take the super-efficient underground systems that drip water directly to the plants’ roots. Jonathan Aguilar, a water resources engineer with Kansas State University in Garden City, calls them the Cadillac of irrigation. But he estimates only around 5% of western Kansas farms use them.

Other tools that don’t cost much to implement, such as soil moisture sensors, can make an immediate impact by helping farmers know exactly how much water each piece of ground needs.

“It gives them a good, healthy sleep at the end of the day,” Aguilar said. “It’s not a guessing game anymore.”

Some farmers, Aguilar said, likely start irrigating earlier than they need to in the spring or keep watering longer than needed in the fall. For nearly half of irrigation systems, he said, conserving could start with just making sure they have the right amount of water pressure — both too much or too little pressure can hurt efficiency.

Anything we can do now to conserve water buys the state critical time to avoid hitting the aquifer’s point of no return.

“We are not yet there,” Aguilar said. “But we are headed there if we don't make any changes.”

The disconnect

But telling Kansas farmers how much of their water they’re allowed to use will never be easy.

Stafford County Republican Brett Fairchild is one of six House lawmakers who voted against the groundwater district legislation. People in his part of the state, he said, worry the bill could grease a slippery slope toward state-dictated irrigation restrictions that infringe on their water rights. One constituent he spoke with called the bill a power grab by the Legislature.

“People in my area are pretty skeptical of passing any water bills,” Fairchild said, “because they think that it could result in mandatory water cuts.”

And a new K-State survey of more than 1,000 farmers across the Ogallala region shows a massive disconnect between how many of them believe depletion is a problem and how many believe they are personally responsible for it.

Sociologist Matt Sanderson, who worked on the survey, says that gap hasn’t changed much since the last survey of its kind in 1984.

“People talk about this as a crisis. This is not a crisis,” Sanderson said. “You don’t have a crisis for 40 years. You have a structural problem.”

In that survey nearly four decades ago, 84% of farmers polled said aquifer depletion was a serious or very serious problem. That’s roughly the same percentage of farmers who responded that they were concerned about depletion today.

More than 80% of farmers in the new survey agreed that groundwater should be conserved so that future generations can enjoy the same benefits of life they have had. Further, 90% responded that groundwater is important because it provides tap water for communities, and nearly 80% said because it helps the profitability of farming.

But more than half of farmers — 58% — said they didn’t feel personally responsible for depletion. That includes a majority of the irrigation farmers surveyed. Only 20% said they think they should personally reduce their water use.

But Sanderson is starting to believe that long-held perspectives about water might finally be changing.

Between what he heard from farmers during the survey and what he’s seen happening at the Statehouse this session, he said, Kansas might have finally endured enough drought and enough depletion that this year could be the tipping point.

“The culture is shifting toward a culture of conservation now,” Sanderson said. “The real question is: Is there enough time?”

It’s vital, he said, to make sure farmers know that if they want to conserve water, they’re not on the margins. They’re in the majority.

Saving the Ogallala Aquifer, Sanderson said, will take more than shaming the irrigators who use it. It will require a shift in the broader systems that give western Kansas farmers incentives to grow thirsty crops like corn in this dry region to serve a nation clamoring for cheap beef and ethanol gasoline — the systems that have built Kansas agriculture into a multibillion-dollar enterprise.

“We’ve been wildly successful,” Sanderson said, “and it’s come at a very high cost at the same time.”

The current structure, he said, often keeps farmers running on an “agricultural production treadmill.”

Consumer demand, subsidies, crop insurance, Farm Bill policies and other systems push farmers to produce as much commodity grain as possible, as cheaply as possible. And in a region this dry, irrigation is a shortcut to bigger, better harvests.

“That’s what we’ve decided as a country we want,” Sanderson said. “Should we be surprised that farmers are doing it?”

Back in Wallace County, Wilson cranks his spool to reel up measuring tape from the depths of the Ogallala. As he walks back to his truck, he gets a message from a survey crew member who just checked a well in southwest Kansas where the aquifer level dropped 10 feet in one year.

The goal, he said, should be to stabilize the aquifer’s levels over the next 20 years and then see where things stand. But in order to make it there, this part of western Kansas would need to cut water use by one-third.

It’s a tall order. But, he said, it should be worth it to all Kansans to do what it takes to preserve the aquifer’s remaining water before it’s too late.

“Even though most of the population lives on the other side of the state, we are all Kansans,” Wilson said. “Everybody's gonna feel the pinch if it ever goes away.”

David Condos covers western Kansas for High Plains Public Radio and the Kansas News Service. You can follow him on Twitter@davidcondos.

The Kansas News Service is a collaboration of KCUR, Kansas Public Radio, KMUW and High Plains Public Radio focused on health, the social determinants of health and their connection to public policy.

Kansas News Service stories and photos may be republished by news media at no cost with proper attribution and a link to ksnewsservice.org.